The Cancer Bomb

The Cancer Bomb exhibit project - Cobalt-60 at 60 - celebrated the 60-year legacy of the cobalt-60 cancer therapy technology. The project was a partnership of the Saskatoon Western Development Museum and USask Research Profile and Impact, with sponsorship from Nutrien (formerly Potash Corp).

By Joan Champ, Former Executive-Director of the Western Development Museum, with research support from University of Saskatchewan ArchivesA New Weapon in the War Against Cancer

No, it didn’t bomb countries. In 1951, one of the world’s first cobalt-60 “bombs” for treating cancer was built in Saskatoon by a dedicated team of scientists and one excellent machinist.

Since then, thousands of Canadian cobalt-60 units have provided radiation treatment for millions of cancer patients around the world.

This is very much a Saskatchewan – and a Saskatoon – story.

Medical Pioneers

Between 1924 and 1941, the rate of cancer deaths more than doubled in Saskatchewan. Something had to be done. In 1944, the new government of Tommy Douglas implemented a North American “first” – free cancer treatment to anyone who had lived in Saskatchewan for at least three months.

Then, in 1949, Douglas personally gave the University of Saskatchewan scientists the “green light” to proceed with the development of the cobalt bomb. Douglas’ confidence in the scientists is part of the reason that Saskatchewan is home to the world’s first successful radiation treatment for cancer with the cobalt-60 unit.

The Cobalt Race is On!

There were actually two cobalt bombs in development during the summer and fall of 1951 – one in Saskatoon and the other in London, Ontario. Each had a different design by a different designer, and both were completed and functioning within days of each other.

The Saskatoon team was the first to successfully treat a patient with an accurately calibrated dose of cobalt-60 radiation.

The Cobalt-60 Unit

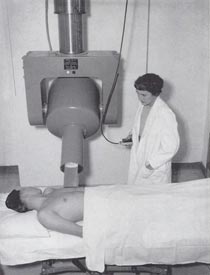

This is the original Cobalt-60 Beam Therapy Unit, known as the cobalt bomb, which was designed, built and operated in Saskatoon.

Unlike the atomic bomb of the Cold War era, this bomb helped rather than harmed people. Radioactive cobalt from the unit attacked tumours that lay deep within the body, thus bringing more cancers within reach of treatment.

In November 1951, the first Saskatoon patient, a 43-year-old mother of four, was treated for cervical cancer with a carefully calibrated dose of cobalt-60 radiation. She lived another 47 years. The cure rate for cervical cancer soon went from 25 per cent to 75 per cent.

How it Worked

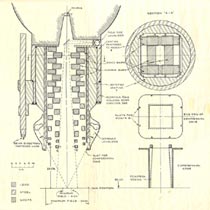

Radioactive cobalt-60 was housed inside the steel-encased lead cylinder that was suspended from an overhead carriage. When the unit was turned on, radiation was directed through the treatment cone towards the patient’s cancer. The size of the radiation beam is defined by a “collimator” designed by John MacKay and Dr. Harold Johns.

The collimator’s lead bars moved in and out, making the radiation beam bigger or smaller, depending on the size of the patient’s tumour. John MacKay’s small Saskatoon shop manufactured over 100 of these collimators for world-wide distribution through the Picker X-Ray Corporation.

The Bomb Builders

Canada’s first full-time cancer physicist, Dr. Harold Johns, and his colleagues at the University of Saskatchewan’s Department of Physics, led the world in the development of high-technology cancer treatment. The Saskatoon team pioneered the world’s first betatron accelerator for treating cancer in

1948-49. Their greatest achievement, however, was the cobalt bomb. It was designed by Johns and built by Saskatoon machinist John MacKay, owner of the Acme Machine and Electric Co. Dr. Johns’ graduate students, including Sylvia Fedoruk, Edward Epp, Douglas Cormack, and Lloyd Bates, assisted with the design and calibration of the machine.

Saskatchewan Leads the Way

Saskatoon’s cobalt unit treated 6,728 patients until it was replaced in 1972, first by another cobalt radiotherapy machine, and later by a linear accelerator. By the 1960s, the cobalt-60 machine was standard equipment for radiation therapy world-wide.

These machines are still in use in many Third World countries that previously did not have the necessary resources for good radiation therapy

Building on the achievements of the 1940s and 1950s, Saskatchewan’s cancer program has grown to become one of the best in the world. Today, the University of Saskatchewan is a centre of excellence for nuclear medicine and research in Canada.